This post may contain affiliate links. Please read our disclosure.

(Managing Dawn Phenomenon with Basal Insulin is excerpted from Think Like A Pancreas: A Practical Guide to Managing Diabetes With Insulin by Gary Scheiner MS, CDE, DaCapo Press, 2011)

The liver is a fascinating organ. It does about a hundred different things. One of its main functions is to store glucose (in a dense, compact form called “glycogen”) and secrete it steadily into the bloodstream in order to provide our body’s vital organs and tissues with a constant source of fuel.

This is what keeps your heart beating, brain thinking, lungs breathing, and digestive system, uh, digesting, pretty much all the time.

In order to transfer the liver’s steady supply of glucose into the body’s cells, the pancreas normally secretes a small amount of insulin into the bloodstream every couple of minutes. This is called basal insulin.

Not only does basal insulin ensure a steady energy source for the body’s cells, it also keeps the liver from dumping out too much glucose all at once. Too little basal insulin, or a complete lack of insulin, would result in a sharp rise in blood sugar levels.

So, you might say that basal insulin and the liver are in “equilibrium” with each other. The basal insulin should match the liver’s secretion of glucose throughout the day and night.

In the absence of food, exercise, and rapid-acting/mealtime insulin, the basal insulin should hold the blood sugar level nice and steady.

Each person’s basal insulin requirement is unique. Typically, basal insulin needs are highest during the night and early morning, and lowest in the middle of the day. This is due to the production of blood sugar–raising hormones during the night, and enhanced sensitivity to insulin that comes with daytime physical activity. Two hormones in particular – cortisol and growth hormone – cause the liver’s natural ebb and flow in glucose secretion.

During a person’s growth years (prior to age 21), basal insulin needs tend to be relatively high throughout the night, drop through the morning hours, and gradually increase from noon to midnight. Most adults (age 21+) exhibit an abrupt increase in basal insulin requirements during the early morning hours, followed by a drop-off until noontime, a low/flat level in the afternoon, and a gradual increase in the evening. This peak in basal insulin during the early morning hours is commonly referred to as a dawn phenomenon.

Basal insulin can be supplied in a variety of ways. Intermediate-acting insulin (NPH) taken once daily will usually provide background insulin around the clock, albeit at much higher levels 4 to 8 hours after injection and at much lower levels at 16 to 24 hours. Long-acting basal insulins (glargine and detemir) offer relatively peakless insulin levels for approximately 24 hours. Insulin pumps deliver rapid-acting insulin in small pulses throughout the day and night. With a pump, the basal insulin level can be adjusted and fine-tuned to match the body’s ebb and flow in basal insulin needs. It is also possible to combine various forms of long-acting insulin to simulate the body’s normal basal insulin secretion.

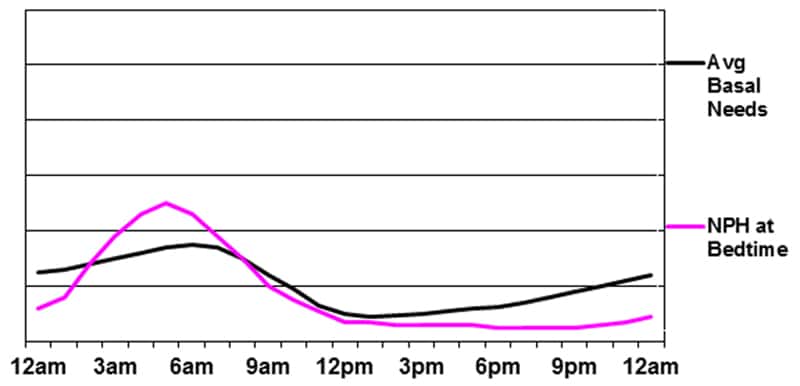

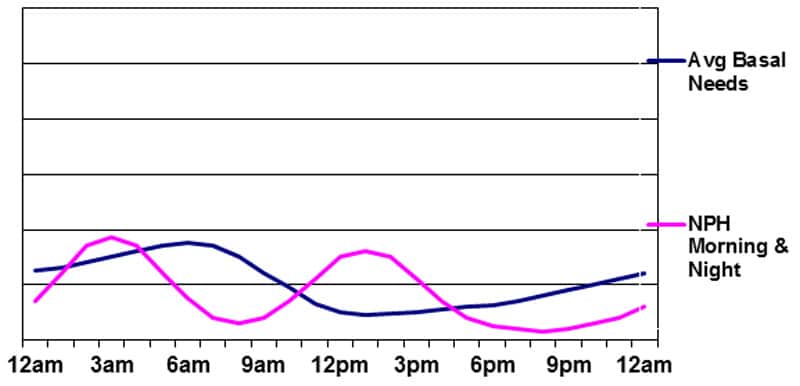

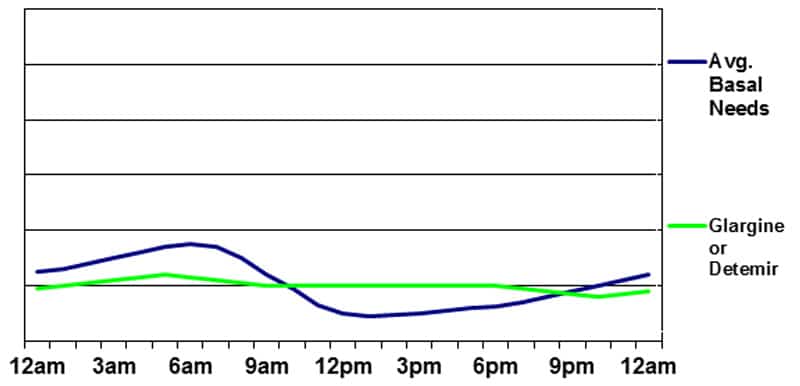

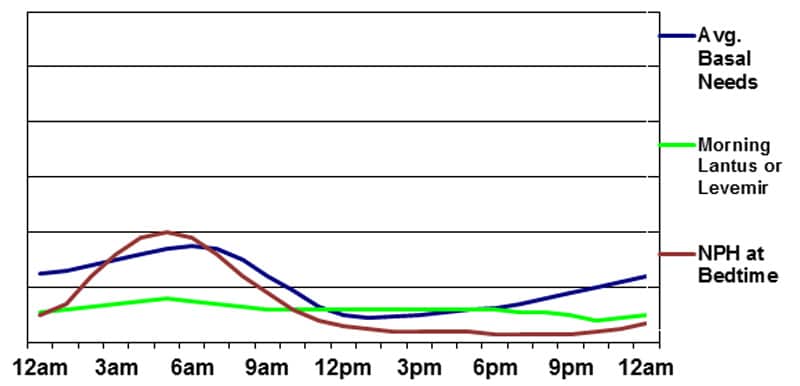

The following figures illustrate the action profiles of various types of basal insulin programs.

Basal insulin supplied by NPH at bedtime

The main advantage of this program is the peak that occurs during the pre-dawn hours. The disadvantages include the unpredictability of the peak (due to NPH’s varied rate of absorption from day to day), the potential for low glucose in the early morning (due to the significant peak during the night) and the likelihood that that late afternoon/evening blood sugar will rise as the NPH tapers off.

Basal insulin supplied by NPH in the morning and evening

The advantages of this program are the peak in basal insulin during the night and the possibility of using the morning NPH peak to cover the carbs eaten at lunchtime. The drawbacks are the same as those in Figure 3 above, plus the major issue of having to conform to a rigid meal/snack schedule during the day due to the peak of the morning NPH insulin. As the graphic clearly shows, this type of basal insulin program does a poor job of matching the body’s needs. It rarely produces stable glucose levels – particularly during the daytime.

Unfortunately, those who use “premixed” insulin twice daily are, essentially, utilizing this approach for their basal program. Each injection of premixed insulin contains anywhere from 50-75% NPH insulin, with the remainder being either Regular or rapid-acting insulin.

Basal insulin supplied by glargine (Lantus) or detemir (Levemir)

Glargine (Lantus) is usually taken once daily, but sometimes is taken twice – particularly when low doses are being used. Detemir (Levemir) is usually taken twice daily, but occasionally can be taken once a day. When basal insulin is injected twice daily, it is reasonable to split the doses evenly and take them approximately 12 hours apart. Taking more in the evening and less in the morning does not usually produce a desired “peak” at any particular time. When taken once daily, it is usually best to take the injection in the morning on a consistent 24-hour cycle. Research has shown that the morning injection has the least potential to cause an undesired blood sugar rise when the insulin is tapering off at around 20-24 hours.

The main advantage of using glargine or detemir is the relatively unwavering flow of insulin (a very slight peak may occur 6 to 10 hours after injection of detemir) and consistent absorption pattern. The disadvantages include the potential for a gradual blood sugar rise during the night (due to the lack of a pre-dawn peak) and around the time of the injection when the insulin is taken once daily (the basal insulin may “wear off” a few hours early and take a few hours to “kick in”). There is also potential for a gradual blood sugar drop in the afternoon as the basal insulin level may exceed the liver’s production of glucose.

Basal insulin supplied by Glargine or Detemir plus Evening NPH

In order to overcome some of the potential problems created by using only basal or NPH insulin to meet the body’s basal needs, it is possible to combine the two. When NPH is added at nighttime, glargine or detemir can be taken once daily at a lower dose than if used without NPH. This minimizes the risk of having glucose levels drop between meals during the day. By adding a modest evening or bedtime dose of NPH, a nighttime/early-morning peak can be achieved. This program offers the unique advantage of allowing day-to-day adjustment of the overnight basal insulin level by making minute changes to the NPH dose without affecting the basal insulin level the following day.

The disadvantages include the need for at least two separate injections and the filling of multiple prescriptions. There is also potential for mixing up doses or taking the wrong insulin at the wrong time since several different types of insulin are being utilized simultaneously.

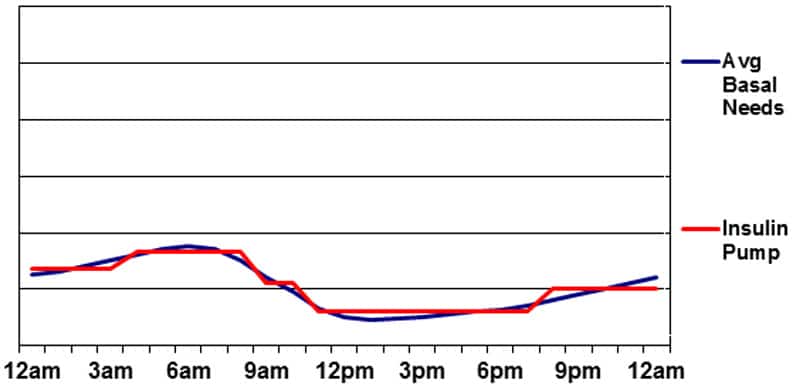

Basal insulin supplied by Insulin Pump Therapy

Pump therapy offers the greatest degree of maneuverability in terms of matching basal insulin to the body’s needs. Because small pulses of rapid-acting insulin are used to deliver basal insulin, variations in peak or action time are not an issue. Changes can be made to the basal insulin delivery on the hour or half-hour, so “peaks and valleys” can easily be built into the program. Pumps also permit temporary changes to basal insulin levels in order to accommodate short-term changes in basal insulin needs (for situations such as illness, high/low activity levels, and stress).

Perhaps the greatest drawback to delivering basal insulin with a pump is the risk of ketoacidosis. Any mechanical problem resulting in a lack of basal insulin delivery can result in a severe insulin deficiency in just a few hours. Without any insulin in the bloodstream, the body’s cells begin burning large amounts of fat (instead of sugar) for energy. The result is the production of acidic ketone molecules—a natural waste product of fat metabolism. This rarely occurs when taking injections of long-acting insulin since there is almost always some insulin working as long as injections are not missed.

Successful pump use will require adequate follow-up and fine-tuning. This should include:

- Basal rate testing throughout the day and night (fasting for 8- to 10-hour intervals and testing blood sugars to see if they are holding steady)

- Fine-tuning of bolus formulas (based on record-keeping)

- Troubleshooting and prevention of emergencies such as DKA (diabetic ketoacidosis); and

- Use of advanced pump features such as extended boluses and temporary basal rates.

Paul Kennedy

Great article. One query – have you experience of Closed Loop pumping and intense exercise? Can be problematic in my experience.

Christel Oerum, MS

Yes, I do find that regular and hybrid closed-loop pumps can have a hard time adjusting to exercise, even when exercise mode is used. If you tend to go low, you can try starting exercise mode ~2 hours before exercise or do manual mode for that period. If you tend to run high, I would skip exercise mode and do a small bolus prior to the workout. I found it more challenging than MDI, but with a bit of experimentation it can be done

Mason Taylor

If I could have afforded a pump and been approved for a pump, I would have been on one long ago. Especially after meeting an Emergency Room tech whose schedule was unpredictable. He told me his job would be impossible without a pump. He might have to work thru any usual coffee break or mealtime. Years earlier a chap working on-call 24/7 as an ambulance attendant had told me the same thing. His job would have been impossible without the flexibility provided by an insulin pump.

Mason Tàylor

As a kid back in the 1950’s I took one big shot NPH first thing in am. Just timing meals and school schedule was challenge enough. Job schedules sometimes resulted in low bg before scheduled lunchtime. Now that I’m retired I can check my blood glucose levels anytime, anywhere and eat or inject or exercise or adjust my schedule for much better time in range (70-130 mg/dL)

. On my last job as a Small Business Administration employee, though I was discrete in bg testing and injections, after several months my supervisor told me I must go to a separate floor to the Nurse’s Office to test and inject, sort of humiliating. Someone feared that I might transmit AIDS with my pre-lunch blood testing or my syringe used for lunch bolus. Eventually the AIDS panic subsided and I resumed testing and injecting at my workspace as before.

Olga

Thank you for this. I’ve had T1 for 38 years and have “dawn lows” (I know!), while my teen son has had T1 for six years and has a pronounced effect (as expected). He’s been on pump for two years with a 6.8 A1c — but at times wants a short pump break (and an emergency plan), without too many days of terrible BGs.

Long intro to express profound thanks for this article — his pediatric endo clinic has been utterly and thoroughly unable to address highly variable insulin needs with basal. I keep being told “Lantus works best once a day, we don’t use NPH because it’s an old style insulin.” (I use NPH + Degludec with great success to avoid overnight lows). When I asked for the logic of once daily lantus, there… was none.

Thanks to Gary and you, I feel much more able to help him if/when another pump break comes along. And I don’t feel like the crazy person ranting about how you can’t match a curve with a flat line.

Christel Oerum

I’m so glad this was helpful! And a little sad that you’re not getting better support at your endo clinic

Ken

Type 1 diabetic for the last 37 years, using a pump since 2006, recently got a CGM (dexcom6) and have only just discovered the dawn phenomenon… Possibly because new job has me getting up at 4:30am and I sleep until 8am on weekends. Workday basal rate has been bonkers, I eat exactly the same foods at exactly the same times and my BG has been going up sharply at 6am… never had that before. Does not happen when I sleep until 8. This was good info, thank you!

Tanya

Hi, I’ve been struggling with DP for a while now. I’m 41 with type 2. My specialist has just started me on detemir once daily at bedtime. He’s started me on 6 units increasing every few days until my morning levels are stable. He’s expecting me to level out between 30 and 40 units each night. Does this sound right? My normal levels through the day were around the 7.5 mmol/l and my morning ones were always med 8 to mid 9s.

Christel Oerum

He is probably calculating the dose based on your weight. I like that he has you increasing it slowly, that way you can stop if you find that you need less, or continue to add if you find that you need more. I wouldn’t worry too much about the amount but rather focus on reaching the blood sugar management that you and your team think is right for you

Lisa

Hi I’m new to all of this. I am type 1 and have been for 40 years. I currently use an insulin pump (Omnipod). I find I am very sensitive to insulin anyway hence the need for a pod. Am I right that during fasting to reduce my basal as if I don’t have many carbs I will hypo?

Christel Oerum

If you go low you have too much insulin onboard, either from your basal or any bolus you might have taken. It’s generally recommended that you consult with your doctor on basal changes if you’re not used to making them on your own

CHRISTINE SNISKY

I take my Lantu and NPH between 10 and 11 at night. my issues with dawn phenom have disapeared. i now wake up with bllod sugars in the 80’s and 90;s. Quite happy with the results!!

Christel Oerum

So glad to hear that!

David R L Worthington

NPH isn’t the only way to manage basal insulin, and it doesn’t do that great a job at its best.

But WHY doesn’t this article so much as mention the possibility of using Regular insulin?

I take it at 5am and again at 8-9 am, and together with either NPH three times a day or Glargine at midnight (bedtime), they produce consequent BG that is perfectly steady (level), ranging between 80 and 120 mg/dl for ten hours straight.

Christel Oerum

Hi David,

Managing Dawn Phenomenon with Basal Insulin is excerpted from Think Like A Pancreas: A Practical Guide to Managing Diabetes With Insulin by Gary Scheiner.

I don’t believe he says that NPH is the only way to manage Dawn phenomenon. He says basal insulin can be supplied in a variety of ways and mentions glargine and detemir in the same sentence

Ann Dillon

Question.

I get taking R at 5 am but again at 8 -9 ?

Struggling with DP now.