You have to love it when research studies come out and prove what you believed all along.

I had this experience when a systematic review and meta-analysis (looking at the results from multiple studies simultaneously) in Emergency Medicine Journal in September 2016 compared the speed of glucose tablets against dietary sugars for treating hypoglycemia in adults who had symptoms of being low.

The dietary forms of sugar tested included sucrose (table sugar), fructose (fruit sugar), orange juice (containing fructose), jellybeans, Mentos, cornstarch hydrolysate, Skittles, and milk.

What the compiled data from four studies suggested is that:

“When compared with dietary sugars, glucose tablets result in a higher rate of relief of symptomatic hypoglycemia 15 minutes after ingestion and should be considered first, if available, when treating symptomatic hypoglycemia in awake patients.”

In other words, glucose worked faster in resolving symptoms of feeling low—and who wouldn’t want to treat a low as quickly as possible?

You can learn more in this video or continue reading below:

Why does glucose work faster?

It’s because glucose is the actual sugar in the blood that you’re trying to raise.

There are three simple sugars in our diet: glucose, fructose, and galactose. Sucrose (table sugar) is a compound sugar that is only half glucose, half fructose.

As shown by its glycemic index, fructose raises blood glucose much more slowly than glucose, likely because fructose has to be converted into glucose. For this reason, juice is not an ideal treatment for hypoglycemia, and it’s very easy to consume too much of it. Milk can also act more slowly (especially if it has any fat in it) because lactose (milk sugar) is half glucose and half galactose.

Some people say that other treatment options work better and faster for them than glucose. That’s not surprising since even this meta-analysis found that neither glucose nor dietary sugars reliably raised blood glucose levels to normal within 10 to 15 minutes.

Since lows occur for all sorts of reasons—including missing a meal, exercising, overestimating insulin needs, and more—how you best treat it depends on a number of factors, and not all treatments are going to work the same in every situation.

The rate at which your blood glucose reaches hypoglycemic levels will also vary, as will how low it goes and how long it will continue to drop.

If you have some glucose handy, though, the fastest way to initially bring up your blood glucose is likely by consuming some straight glucose, which you can get in glucose tablets and gels, Gu (maltodextrin), Gatorade and other sports drinks (glucose polymers), and even Smarties candy (dextrose, another name for glucose).

You may have to follow glucose intake with more glucose, another carb snack, mixed nutrient snack (with some fat and protein), or a full meal, depending on why you went low in the first place.

To treat hypoglycemia, focus on doing three things:

- Raising your blood glucose out of the low range as quickly as possible,

- Not overtreating a low, and

- Not taking in any more calories than necessary.

For these reasons, I recommend using at least a small amount of glucose to initially relieve your immediate symptoms and then deciding—based on when you last ate, what you ate, how much insulin you’ve had, activity levels, etc.—if you need to follow up that up with anything else to fully resolve the low, prevent it from recurring, and not overshoot your blood glucose target.

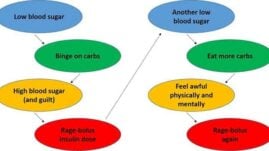

Honestly, there’s nothing worse than feeling low for a long time, except for maybe ending up high later after you’ve eaten everything in sight.

You also don’t want to gain excess fat weight from having to treat too many lows or from overtreating them (requiring more insulin later to bring down highs). Treat them with as few calories as possible for all these reasons! Be prepared and always carry some glucose with you, along with other snacks.

Shirley Butler

I would like to have a diabetic journal like the one shown on your videos! I have been a type 2 diabetic for about 40 years and still do not have good (or great) control. I recently got a CGM, but still not having good control. Any advice (or products) you could advise would be most appreciated!

Thank you! (I am Medicare and any freebies are appreciated also).

Christel Oerum, MS

Sometimes your doctor’s office can give you a free diabetic journal. The one I have I sell through Amazon (https://a.co/d/9E1pNu1) for $6.99

Ranjeet S. Tate

Glucose tablets seem too bulky to get the ~15 gm of glucose for a low?

Felicity

I’m diabetic 2 on daily insulin I get so confused nd depressed with this diabetes on the lows nd highs of it trying my best to control it J appreciate what I’ve read now thanks

Judie

I always drink orange juice with some pulp. It works for me.

Gail Belles

Informative article, thank you! I’ve experienced many low glucose readings over the 30+ years of dealing with Type 1 diabetes and I explain to my endo over and over again that eating 15g of carbs and waiting 15 minutes before taking anything else to treat the low does not work when the blood glucose continues to drop. I constantly struggle to lose weight and find that when I treat lows I end up eating way too many carbs to get the blood glucose back into normal range. I hope this research continues to gain insights on how to treat lows correctly to avoid overeating carbs and associated weight gain concerns in conjunction with widespread awareness of the results of the research to help all of us who deal with these issues sometimes multiple times a day!

Ava

I agree but has I so learned – lows pull the potassium into your cells leave you without serum potassium. It is important to replace potassium after a low. After a couple of glucose tabs, OJ or unsweetened coconut water is my go to replacement.

Julie M Elander

That’s great to know, Ava. Thanks!

Jane

My 17 year old grandson was recently diagnosed with type 1 diabetes- I have been experiencing with recipes for low carb dishes and have been very disappointed in my overall results

Today I made mashed cauliflower – cook 1 head cauliflower using a steamer basket until tender- drain throughly- getting all water out – add 2Tbs butter, 1/4 cup sour cream – 2 oz cream cheese – using hand mixer- beat as you would mashed potatoes until smooth- place lid on pot and put back on burner for about 5 mins- serve hot

With about 7 carbs per serving I considered this one a success- everyone ate this dish and liked it

Julie Elander

That’s great to know!

Thanks!