If you live with diabetes, you may have heard of the term “DIY Looping” but may not have any idea what it actually is.

DIY Looping is the process by which someone with diabetes “hacks” their existing insulin pump with a single-board computer, such as a RileyLink or Raspberry Pi.

This essentially makes your insulin pump communicate with a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) to make basal insulin adjustments automatically, instead of manually suspending, reducing, or increasing insulin throughout the day.

This is a popular and growing movement and has helped countless people improve not only their blood sugars but their emotional and mental health as well.

In this article, you will learn what DIY looping is, how it works, the pros and cons, and lessons learned from a year of looping myself.

What is ‘looping’?

The term “looping” refers to, “closing the loop” between one’s insulin pump and a continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) system.

Currently, many insulin pumps do not communicate with existing CGM systems, and no tubeless insulin pumps exist that communicate with CGMs.

Your CGM may read that your blood sugar is 60, but you need to manually suspend insulin and/or eat a snack to remedy your hypoglycemic reading.

On a looping system, your CGM would tell your insulin pump that your blood sugar is running low, and your insulin pump would suspend insulin immediately until your blood sugar started to rise again.

It’s important to note that this is NOT FDA approved, so all risk and liability is on the user if they decide to build their own system.

How did this come about?

This movement stemmed from the frustration and disappointment people with diabetes have felt for a long time at the pace that technology (that has the potential to completely change lives) was being developed.

Looping is the brainchild of many brilliant people and families affected by diabetes who started the #WeAreNotWaiting movement nearly a decade ago.

The hashtag was coined in 2013 at the first-ever DiabetesMine D-Data ExChange gathering at Stanford University by Lane Desborough (Chief Engineer at Medtronic) and Howard Look (CEO of Tidepool).

Looping is part of the larger Open Artificial Pancreas System (OpenAPS) movement where advocates in the diabetes community are developing opensource platforms, code, and apps to essentially reserve-engineer existing durable medical equipment (like older insulin pumps) to help people living with diabetes achieve better health outcomes when FDA-approved devices have proven inadequate.

Dana Lewis and Scott Leibrand of Seattle, Washington, were the first couple to develop the OpenAPS, a homemade artificial pancreas, for her own diabetes management.

It is now being used by thousands of people around the world, and many more developers have added onto and built upon the original code, improving the system with each software update. Nate Racklyeft has written a great piece on the history of Loop.

In 2014, diabetes advocate, Anna McCollister-Slipp, told Forbes:

“Everybody seems to think that it’s okay to wait another two or three years for this process to play itself out. In terms of the business or policy cycles, that’s the current trajectory, but for those of us who live with this data dysfunction, two or three years can make the difference between going blind or dying in our sleep. It’s purely an issue of priorities and urgency and despite glowing rhetoric to the contrary – patient needs are nowhere in sight for manufacturers or policymakers.”

The OpenAPS community wanted to change that.

What does the system do?

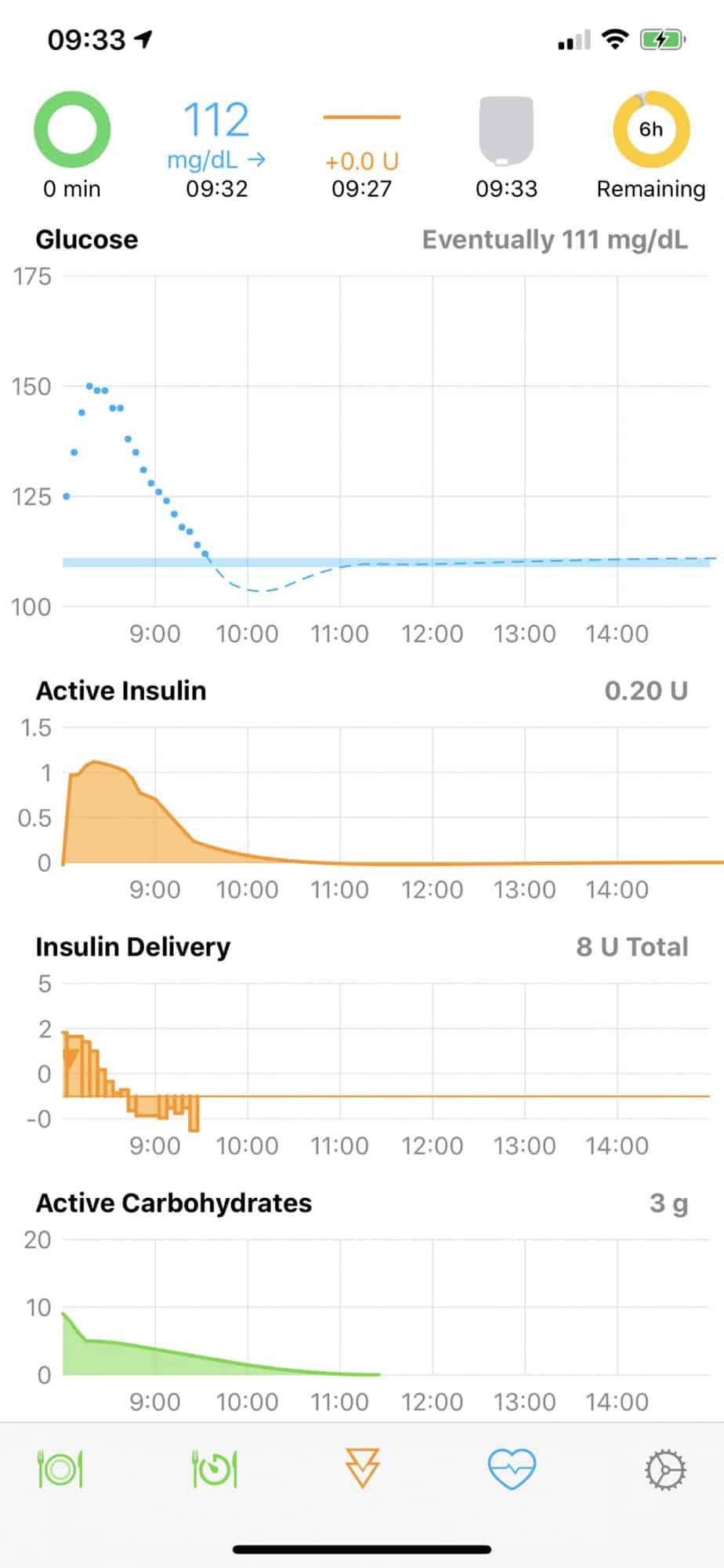

When you build the system, all of which is free to download with instructions available online, you will see that the DIY loop system immediately starts reading your blood sugars off of your CGM, and transmits that data to an app on your phone (that acts as an insulin pump now).

The system makes adjustments automatically (that you set up with your correction factor, insulin to carbohydrate ratios, etc.), but it doesn’t account for food eaten.

You still need to bolus like normal for carbohydrates, hence the “hybrid” closed-loop system. There is currently no completely closed-loop system that would essentially use artificial intelligence (AI) to predict food or exercise.

Studies have shown that DIY APS systems improve not only time-in-range for people with diabetes, but also vastly improve quality of life.

In a 2016 self-reported outcomes study, 56% of DIY loop users reported a large improvement in sleep quality.

A type 1 parent, Dr. Jason Wittmer, tracked his son’s school nurse visits: before OpenAPS, his 4th-grade son averaged 2.3 visits per day (420 total in a school year); after OpenAPS, his son visited the school nurse 5 times during the entire school year.

Families using DIY loop systems also report less time spent talking about diabetes and improved family communication around diabetes.

They also report improved sleep quality for multiple family members (not only the person living with diabetes) and spending less time thinking about diabetes and doing diabetes-related management tasks, such as treating lows or sitting out of sports due to highs.

How do you build your own system?

This part gets complicated but is doable even for a novice. The OpenAPS community firmly believes in keeping OpenAPS open source, for all to use.

The beauty of this community is everyone’s willingness to help one another to achieve better health outcomes. The community has created and maintains the online instructions to build your own system at a website called LoopDocs with a thorough explanation of the process and FAQ.

To get started, though, this is what you’ll need to build your own DIY loop:

- A compatible insulin pump and continuous glucose monitor system

- A RileyLink single-board computer (they sell for about $150)

- An iPhone

- A compatible Macbook computer

- Apple developer account, and download the Xcode app

Since this system is not FDA approved, each user needs to build the code for their own insulin pump, but LoopDocs makes that easy and accessible, with all instructions available online.

You can build the program within 3-4 hours and can start creating your settings by simply transferring your existing insulin pump settings right into the new Loop app on your iPhone. The settings you set yourself are:

- Target blood glucose

- Target exercise blood glucose

- Pre-meal target blood glucose

- Correction factor

- Standard basal rates for different times of day

- Insulin to carbohydrate ratio (can change for different meals)

Once you finish installing Xcode and building the Loop app, you can either opt for an “open” loop mode or “closed” loop mode.

The open-loop mode merely gives you suggestions for dosing but doesn’t actually override your regular basal insulin pump program, whereas if you “close the loop” the new settings on your Loop app will override your old basal program.

It’s important to remember that your RileyLink hardware needs to be in close proximity to your iPhone at all times. Your iPhone now serves as your new insulin pump and all dosing decisions are made from the app on your phone.

If your RileyLink is ever out of range for an extended period of time, your basal settings will simply revert back to your original insulin pump settings automatically. You will not be without basal insulin.

Once you do that, you’re done and are now officially looping!

What is the biggest difference between Looping and not?

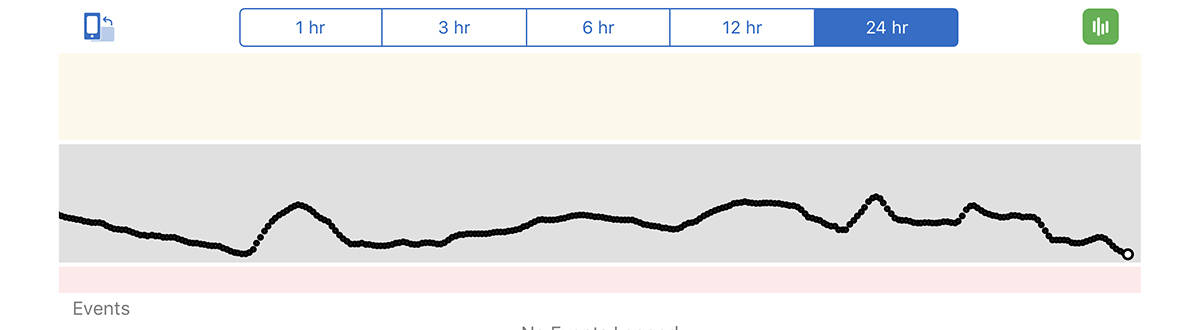

I’ve been looping for a little over a year now, and I’ve noticed the biggest difference in my overnight blood sugars.

Since this is a hybrid closed-loop system (and not a completely closed-loop that would dose insulin for food and adjust insulin for exercise automatically), the system performs best when there are fewer variables.

I’ve noticed that I require a lot more basal insulin overnight to help combat the dawn phenomenon, which I used to struggle with, but don’t worry about anymore.

Looping has also helped me improve my time-in-range and greatly has decreased the number of hypoglycemic events I have per week (down from 2 to 3 per day to 1 or 2 per month) while achieving my lowest hba1c ever, 5.9%.

Exercise and eating are easier with the loop, too. I can set exercise mode on the app an hour before I begin an exercise, and I rarely go low.

When I am eating a meal, if my carbohydrate count is slightly off, the loop will increase my basal to make up for it, without sacrificing good blood sugar.

The system isn’t perfect

The system has been absolutely mind-blowing, and I am so thankful for all of the smart, kind, and generous people who have shared it with the world, but it’s still not perfect.

Since the loop makes basal adjustments based on your CGM readings, the system is only as strong as your weakest CGM site. Any time I have an error on my CGM, or a site falls out, the loop will disconnect.

This also happens every 10 days when it’s time to change to a new CGM site during the 2 hour warmup period where you do not have blood sugar readings.

Additionally, sometimes CGM readings can be off or completely wrong, in which case your pump is making adjustments on faulty data.

So thankful for this life-changing technology

In the end, looping has only made my life with diabetes easier. I get to live a more carefree existence, one where I don’t have to micromanage my care 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

When I’m hiking with my husband in the mountains of Colorado or on vacation at the beach, I trust that my blood sugar is quietly humming along in the background, and I worry about going low and high less often.

It feels great to know that the technology I trust is making dosing decisions based on the amount of insulin I already have “on board”, what my correction factors are, and what time of day it is, and it creates more space in my brain for other, non-diabetes related things, like life, work, family, and fun.

I am anxious for an FDA-approved tubeless hybrid closed-loop insulin system (not to mention a cure!), but until then, I’m a bonafide looper.

Shauna cohn

YES YES YES! This article omg I looove it.

I knew 15 years ago that a pump would absolutely change my life but could never afford one and so, I kept on with my mdi’s eventually falling into needle phobia and just not eating so I didn’t have to have an injection all the time.

The stress and worry of all this take a toll as anyone with diabetes would know and whilst I never got sick, I was sick all the time just generally, if that makes sense.

I ended up having a career change at the age of 55 and went into mining driving trucks – well that was difficult but I managed! And then I met an angel on a mine site whose son had diabetes and had been on pumps all his diabetic life (our kids today with diabetes are so so lucky).

Anyway he GIFTED me an old Medtronic paradigm and just as I KNEW my life changed! I ate whatever I want and bloused the GUTS out of my pump (I didn’t even know what a bolus was before) cause the language of diabetes had changed so much over the years of me having it and being blissfully ignorant!

Anyway today I still have that pump but it gave up the ghost – I DO have another paradigm (which was also given to me) BUT was gifted not that long ago with a new minimed 670g and THATS a story for another day too.

I don’t like this pump as much but am pretty sure I can do the looping thing on it. But, I’m terrified as I would have to do it alone and I’m afraid I just don’t understand it all!!!

But yes in my journey of diabetes with shauna cohn the pump has made the ABSOLUTE difference between life and death for me this I know and I LOVE the social media of diabetes now – haven’t embraced it fully but it’s there like the air we breathe and I know if I have to I can at anytime contact anyone and I will get help – just not sure about the looping help cause I won’t understand the jargon!!! So glad for this excerpt thanks for writing it.

Tamer

I have accu chek solo pump can i make for it loop system with free style libre or not and if i can how to make it

Christel Oerum

Check out the OpenAps site (https://openaps.readthedocs.io/en/latest/docs/Gear%20Up/pump.html) for guidance. Below the flowchart, they do mention the Roche Accu-chek Combo

Brooke Clay

I’m certainly looking forward to an FDA-approved, tubeless closed loop system as well! I love having Omnipod for the beach days when I’m spending lots of time in the water. Do you notice you have less control over your blood sugars on beach days if you are in the water and not withing range of your devices?

Christine

Thanks for the comment! Since I loop with the Omnipod and Dexcom, whenever I’m not near my Riley Link or iPhone for a little while (like being in the water), the system reverts back to the original basal settings that I have programmed in my PDM, so I usually don’t have issues. That being said, I am definitely more likely to go low (with exercise, etc.) if I’m not near my devices, because my basal rates won’t adjust for exercise if I’m out of range. Hope that makes sense!

Brenda Huberts

Thank you for this very informative & helpful article!

So many questions answered about the looping thing!

I have a question though, why do I need a Mac book? If I have a newer version iPhone and a normal laptop, would that be good enough?

Also can I use the freestyle libre on this system?

Christine Fallabel

Hi, Brenda!

Thanks for the thoughtful comment and question. You need a MacBook because you need to use Xcode to write and build the app for the iPhone, which you can’t do on a regular computer. If you want to try with a PC, it’s technically possible, but there are a lot more steps involved (downloading a program that acts as a MacBook on your existing PC, etc.). And the DIY Loop only works with Dexcom, but hopefully there will be builds in the future that can incorporate the Libre!

SABAA

hey actually it work with libre (+ 3rd party device like miaomiao or bubble)

Shauna

It does? And that’s what you use?